By Dr Sonia Lee Vern Chien and A/Prof Dr Eshamsul Sulaiman

Abstract

Dental injuries leading to tooth loss and subsequent extractions can have significant biological, physical, and psychosocial impacts, compounded by progressive volumetric deficiencies in hard and soft tissues at the extraction site. The complexity of restorative procedures increases in areas where aesthetic demands are high. This case report details the meticulous treatment planning and execution involved in replacing a missing tooth with an implant, complemented by periodontal plastic surgery and an eight-unit fixed prosthesis to enhance aesthetics outcome.

The treatment plan began with a comprehensive examination and diagnosis, emphasizing aesthetic considerations such as the smile line, transition zone, zenith positioning, and tooth proportions. Prior to implant placement, the endodontic and restorability status of the maxillary left central incisor was assessed, and an apicoectomy was done prior to implant placement. To achieve the ideal implant positioning, a computer-aided implant surgery (CAIS) was done to achieve an ideal four-dimensional position. Aesthetic outcomes were further enhanced by peri-implant plastic surgical reconstruction with autologous soft tissue grafting, and the soft tissue was meticulously contoured with customized provisional implant-supported crown.

The digital workflow allowed for precise control from planning to execution. With this, the case was completed with a customized implant abutments and individually milled crowns that fulfilled the planned aesthetic, functional, and health goals. The patient expressed satisfaction with the outcome and was provided with a bilaminar layered maxillary occlusal splint for night-time use, along with a strict six-month recall schedule.

Introduction

The discovery of osseointegration with dental implants was first reported by Brånemark in 1971. This finding has since had a profound impact as an alternative modality to replace missing tooth. Sustaining a traumatic dental injury resulting in the loss of a tooth especially in the aesthetic zone have significant physical and psychosocial consequences to an individual.1

After an extraction of a tooth, alveolar ridge deformities or defects are often present after a tooth extraction which is common in ninety-one percent of cases.2 Most studies have reported that the greatest amount of bone volume loss of 25% occurs in the first year after tooth extraction, increasing to about 40% loss in 3 years.3,4,5 Its volumetric deficiency often leads to soft and hard tissue deficiencies, which can significantly impair the success rate of the case.6,7.

Restoring an aesthetic case becomes increasingly complex when it involves multiple teeth and implant. To achieve the aesthetic and functional goals, there must be coherent considerations with the smile planning, prosthetic considerations, and the implant must be placed in a prosthetically and biologically driven position taking into considerations of hard and soft tissue augmentation, as well as the timing, abutment planning, soft tissue contouring with provisionals and finally the definitive restoration.

Background

A 42-year-old Chinese female presented to the dental clinic with concerns about her front tooth, “I have been living with this piece of denture for many years and has significantly impacted my confidence”.

The patient had lost her maxillary right central incisor due to a traumatic accident 20 years ago, leading to its replacement of the missing tooth with a removable prosthesis. Additionally, the patient underwent a root canal treatment followed by the placement of a crown for the maxillary left central incisor.

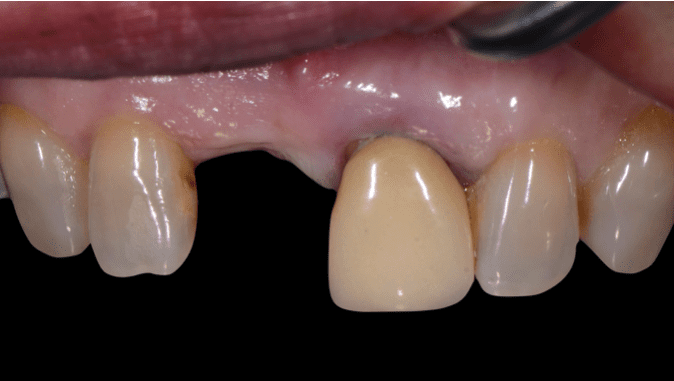

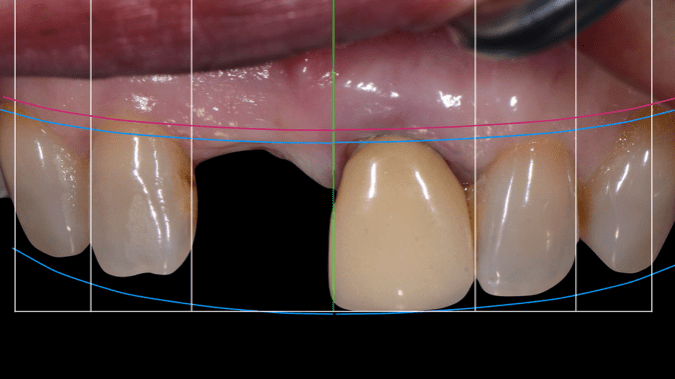

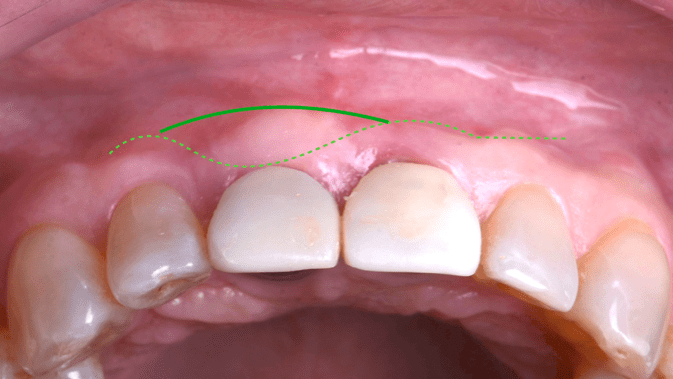

Clinically, the patient presented with an Angle’s Class II incisal relationship, deep overbite (5mm), moderate smile line8, and the gingival zenith position (GZP) disharmony in position and long axis of the teeth. Her oral hygiene was fair, healthy moderate periodontal biotype, scalloped gingival tissues and caries free. The maxillary left central incisor was restored with a porcelain fused to metal (PFM) crown which appeared more opaque, lack of translucency than the adjacent teeth and also with 0.5mm of gingival recession exposing underlying discoloured root (Figure 1). A significant amount of horizontal bone defect revealed a Seibert Class I bone defect9 over the edentulous site.

Radiographic Examination

Radiographically, maxillary left central incisor presented with a 3mm peri-apical radiolucency, radio-opaque root filling material with adequate length, taper and density and a radiopaque post and crown. A 20% mesial and distal bone loss was observed.

Treatment Planning

Initial Assessment, Assessment of Abutments

Initial treatment plan started with a thorough examination and aesthetic evaluation of the smile line in relation to planned gingival margin, tooth proportions, level of the zenith and occlusion. The zenith of maxillary left central incisors was positioned 1mm coronal from the ideal position. A series of photographs and 3D scans was taken, followed by smile planning with ideal contours, proportion, length, shape and position was done (Figure 2).

Before implant placement, adjacent abutments were access to determine its prognosis, which could influence the treatment planning, sequence and execution. According to the current best evidence, surgical endodontic retreatment with root end filling with white ProRoot MTA (Dentsply, Tulsa, OK, USA) was indicated due to the a functional prosthetic crown with adequate coronal seal and satisfactory radiographic evaluation of the obturated root canal.10,11

3D Data Acquisition, Planning and Surgical Guide

The success in implant therapy especially in the aesthetic zone is a harmonious relationship between the implant position, soft tissue, hard tissue and final implant-supported restoration.

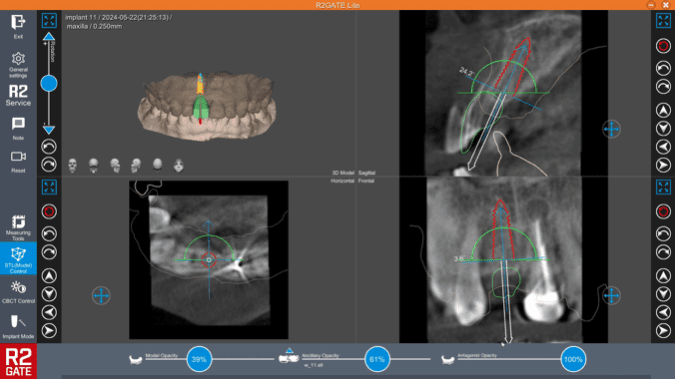

3D data were acquired in Digital Imaging and Communication in Medicine (DICOM) format, alongside 3D scan of the models in Stereolithography (STL) file derived from the desktop scan. R2Gate® software was used for aligning the data acquired and implant planning. Implant position was planned based on a prosthodontic driven treatment planning between the best possible position in the bone in a four-dimensional perpective12 (Figure 3).

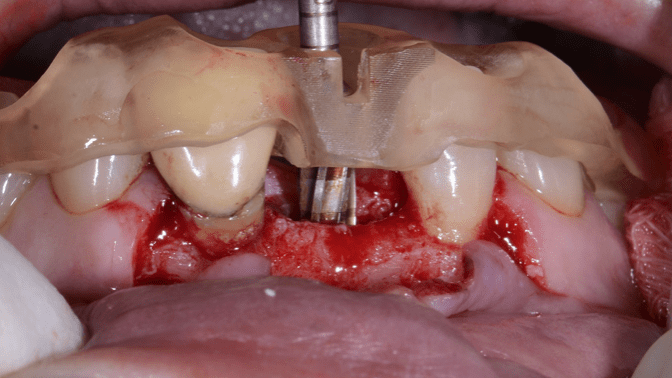

The tooth-supported surgical guide was designed as an extended resin block that contained the surgical sleeve therefore no metal sleeves were needed with the R2GateTM (Megagen Implant, Daegu, Korea) implant planning software (Figure 4). The guide was than 3D-printed and its fit was verified on the cast model and patient’s mouth.

Surgical And Prosthetic Procedures

Fully Guided Implant Placement with Simultaneous Guided Bone Regeneration

On the day of surgery, the guide was passively seated to ensure fit. Pre-operative instructions and consent was taken, followed by administration of local anaesthesia by infiltration (Articaine Hydroclhoride 4% with Adrenaline1:100,000, Septanest, Septodont Ltd, UK). Full thickness mucoperiosteal flap was then reflected on the buccal side to assess the defect and a horizontal periosteal releasing incision with submucosal detachment was done to ensure a tension free flap.

Osteotomy was prepared with sequential bone drilling protocols using the R2GATE® surgical kit. The final fixture dimensions were 3.7mm x 11.5mm Megagen BLUEDIAMOND® regular thread, with final torque of the 45Ncm. The implant was positioned through the guide and a healing abutment (5mm diameter x 3mm height) were screwed into the implant. Simultaneous guided bone regeneration (GBR) using 0.15g of bovine bone substitute (MedPark S1 Dental; Medpark, South Korea) was used, and the site was covered by a resorbable collagen membrane 1.5x3cm (Lyoplant© Braun Dexon, Germany), followed by tension free flap closure. The patient received an immediate 3D-printed provisional cantilever prosthesis from maxillary right central incisors (Figure 5).

Osseointegration Period and Soft Tissue Augmentation

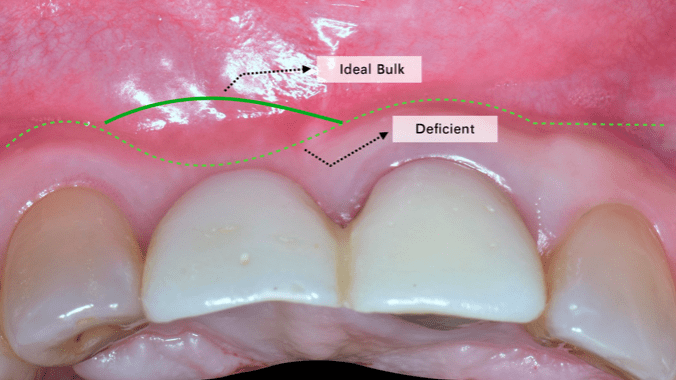

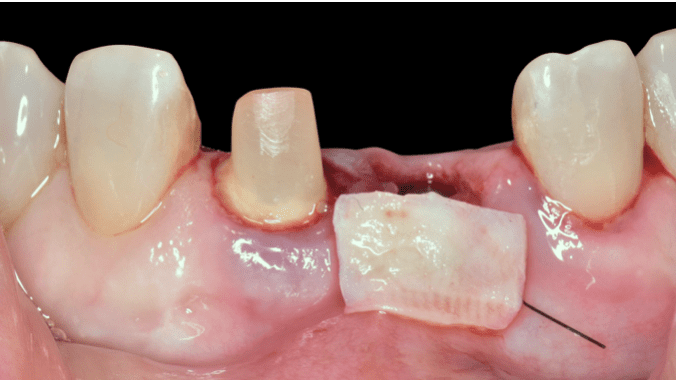

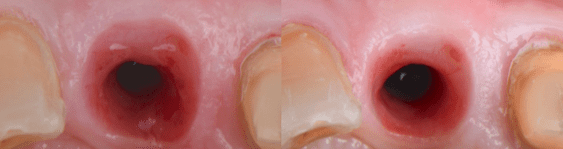

Nine months after implant insertion, second stage surgery and connective tissue graft were performed, followed by a provisional implant supported crown under local anaesthesia (Articaine Hydroclhoride 4% with Adrenaline1:100,000, Septanest, Septodont Ltd, UK). A roll-flap technique with de-epithelization was first performed, followed by removal of the healing abutment. Due to the lack of horizontal soft tissue volume and contour, a periodontal plastic surgery was performed where the connective tissue graft (CTG) was harvested from the patient’s palate (Figure 6,7,8). Two vertical and horizontal incisions were made resulting in a rectangle graft and further de-epithelialised outside the mouth using a new scalpel blade 15c. The CTG was secured to the implant supracrestal site using a tunnelling technique, to further increase the soft tissue thickness and to achieve better aesthetic outcomes.

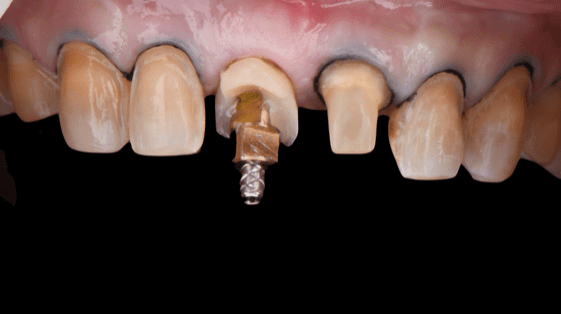

Soft tissue healing and maturation was allowed before soft tissue contouring of the emergence was done with an implant provisional, with simultaneous preparation of the rest of the teeth and fabrication of the provisional crowns (Figure 9).

Master Impression and Final Restoration

Patient was allowed to function with the provisionals for at least four months (Figure 10). A hybrid workflow was used to achieve the desired occlusion and aesthetic. The final restoration included an independent cement-screw-retained implant prosthesis on a hybrid titanium stock base and zirconia coping. The total prosthesis included four lithium disilicate crowns, and four lithium disilicate crowns. Patient was satisfied with the final aesthetic outcome and the restoration remained stable during regular six-month recall appointments.

Discussion

Rehabilitation of an aesthetic case, particularly those involving multiple restorations, require meticulous planning and considerations. During the initial phase of treatment planning, Magne and Belser have stress that one off the key aesthetic consideration was the gingival morphology, contour and health. The gingival zenith, the most apical point of the gingival margin’s curvature, plays a crucial role in determining the desired axial inclination and position of the tooth. This serves as a critical starting position on the intended final restoration in this case. In the implant planning, the depth of the implant serves as the most critical dimensional position especially in the aesthetic zone. The future planned gingival margin of the implant and zenith serves as the reference point. Literature and consensus suggest that the implant should ideally be placed 3-4mm to this reference point. This depth allows proper emergence to be formed and adequate tissue thickness to maintain tissue stability.

Following tooth extraction, the loss of periodontal ligament, bone and surrounding structures leads to significant volumetric changes that can impact restorative outcomes. In this case, GBR and soft tissue augmentation were essential. The decision to perform implant placement with simultaneous GBR using xenograft was driven by the localized concave defect on the buccal side. There was no implant thread exposure. However, due to thin facial bone, xenograft putty was used to increase the bone thickness following decortication. Literature has demonstrated comparable outcomes in bone augmentation with xenograft and autogenous.13 For successful GBR, stabilizing the bone grafts and protecting it from soft tissue growth are critical with the use of a barrier membrane.14

Further soft tissue corrections, there are plethora ways to reconstruct these loses. Autologous connective graft is considered to be the gold standard in periodontal plastic surgery and highly effective.15 A roll flap technique and CTG harvested from posterior lateral palate with free gingival graft that was de-epithelized extraorally was used in this case to achieve the desired outcome. In addition, the soft tissue was further contoured with the help of the provisional prosthesis. The provisional prosthesis further contoured the soft tissue, and evidence suggests that a concave sub-critical contour maximized soft tissue height, stability and thickness (Figure 14).

Finally, while the conventional workflow has been a standard of practice and extensively researched and optimized for clinical performance, the digital workflow has been gaining traction and said to offer advantages such as reducing working or production time and increasing patient comfort. A hybrid workflow, combining the strength of both conventional and digital approaches, was employed in this case to enhance treatment predictability (Figure 13).

Peri-implantitis, the most common cause for late implant failure. Current systematic review and consensus, show no significant difference between screw or cement retain prosthesis in preventing peri-implantitis. Therefore, careful design of the final prosthesis was taken into consideration to prevent cement extrusion to the peri-implant tissues. The final crown margin on to the hybrid zirconia coping was design to be supragingival, facilitating easy removal of excess cement.

<< Back to Contents Menu

EDITOR’S PAGE | ADVISORY BOARD | NEWS | PRODUCTS | COVER FEATURE | CLINICAL | PROFILE | EXHIBITIONS & CONFERENCES | PRACTICE MANAGEMENT

Aesthetics is a crucial aspect and are synonymous with natural and harmonious appearance. To meet the aesthetic demands of this case, all-ceramic restorative materials were selected to achieve a natural translucency, resulting in the 8 units monolithic milled lithium silicate cemented with the proposed protocol of cementation (Figure 15).

In conclusion, aesthetic rehabilitation involving multiple restorations and prostheses requires a multidisciplinary approach and consideration. The success rate of such treatments can be significantly increased with proper planning. By integrating advancement in digital tool and conventional workflow, a hybrid workflow ensures a predictable outcome (Figure 16,17).

References

1. Baxevanos K, Topitsoglou V, Menexes G, Kalfas S. Psychosocial factors and traumatic dental injuries among adolescents. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2017;45(5):449-57.

2. Abrams H, Kopczyk RA, Kaplan AL. Incidence of anterior ridge deformities in partially edentulous patients. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry. 1987 Feb 1;57(2):191-4.

3. Carlsson GE, Bergman B, Hedegård B. Changes in Contour of the Maxillary Alveolar Process Under Immediate Dentures a Longitudinal Clinical and X-Ray Cephalo-Metric Study Covering 5 Years. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica. 1967 Jan 1;25(1):45-75.

4. Tallgren A. The continuing reduction of the residual alveolar ridges in complete denture wearers: a mixed-longitudinal study covering 25 years. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. 2003 May 1;89(5):427-35.

5. Pietrokovski J, Massler M. Alveolar ridge resorption following tooth extraction. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry. 1967 Jan 1;17(1):21-7.

6. Papaspyridakos P, Chen CJ, Singh M, Weber HP, Gallucci G. Success criteria in implant dentistry: a systematic review. Journal of dental research. 2012 Mar;91(3):242-8.

7. Schropp L, Wenzel A, Kostopoulos L, Karring T. Bone healing and soft tissue contour changes following single-tooth extraction: a clinical and radiographic 12-month prospective study. International Journal of Periodontics & Restorative Dentistry. 2003 Aug 1;23(4).

8. Tjan AH, Miller GD, The JG. Some esthetic factors in a smile. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry. 1984 Jan 1;51(1):24-8.

9. Seibert JS, Salama H. Alveolar ridge preservation and reconstruction. Periodontology 2000. 1996 Jun;11(1):69-84.

10. Karabucak, B.; Setzer, F. Criteria for the ideal treatment option for failed endodontics: Surgical or nonsurgical? Compend. Contin.

Educ. Dent. 2007, 28, 304–310.

11. Comparison of endodontic failures between nonsurgical retreatment and endodontic surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis

M Dioguardi, C Stellacci, L La Femina, F Spirito… – Medicina, 2022 – mdpi.com

12. Funato A, Salama MA, Ishikawa T, Garber DA, Salama H. Timing, positioning, and sequential staging in esthetic implant therapy: a four-dimensional perspective. International Journal of Periodontics & Restorative Dentistry. 2007 Aug 1;27(4).

13. Kim YJ, Saiki CE, Silva K, Massuda CK, de Souza Faloni AP, Braz-Silva PH, Pallos D, Sendyk WR. Bone formation in grafts with bio‐Oss and autogenous bone at different proportions in rabbit calvaria. International Journal of Dentistry. 2020;2020(1):2494128.

14. Wang HL, Boyapati L. “PASS” principles for predictable bone regeneration. Implant dentistry. 2006 Mar 1;15(1):8-17.

15. Zucchelli G, Tavelli L, McGuire MK, Rasperini G, Feinberg SE, Wang HL, Giannobile WV. Autogenous soft tissue grafting for periodontal and peri‐implant plastic surgical reconstruction. Journal of periodontology. 2020 Jan;91(1):9-16.

Sonia Lee Vern Chien (BDS, MFDS RCS (Edinburgh), MDS Prosthodontics, Singapore)

Dr. Sonia Lee graduated with a bachelor of dental surgery from the Penang International Dentistry College Malaysia and is a member of the Royal College of Surgeons Edinburg . She has completed her advanced speciality training and obtained per Masters of Prosthodontics from the National University of Singapore.

Dr. Sonia has a special interest in complex prosthodontics training, dental implants, dental aesthetic, digital dentistry, contemporary materials and also takes a special interest in dental photography. She currently works at Clarity Dental Clinic together with a team of clinicians trained in different specialities sharing a similar vision, mission and treatment philosophy.

Eshamsul Sulaiman [BDS (UK), MFD.RCS (Ireland), MClinDent (Distinction in Prosthodontics, London)]

Specialist and Senior Consultant Prosthodontist, Head of Implantology Unit, Department of Restorative Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Malaya

Dr. Eshamsul Sulaiman is an Associate Professor at the Department of Restorative Dentistry, University of Malaya. He graduated with BDS from the Queen’s University of Belfast, United Kingdom in 1997 and obtained his specialist training in Prosthodontics with Distinction from the Eastman Dental Institute, University College London, United Kingdom in 2004. His early training was in the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery and Restorative Dentistry at the University Dental Hospital, Cardiff, United Kingdom from 1997 to 2001. He obtained the Membership of the Faculty of Dentistry (MFD) from the Royal College of Surgeons, Ireland in 2000.

Dr. Eshamsul has 20 years’ experience in oral implantology and has been actively involved in the teaching of postgraduates in Oral Implantology since 2005. Dr. Eshamsul has performed a variety of complex implant procedures involving guided bone regeneration (GBR), connective tissue grafting, sinus floor elevation, alveolar ridge preservation & augmentation, immediate implant placement in the aesthetic zone, partial extraction (root membrane) technique as well as managing mechanical complications post implant placement. He also incorporates computer-guided implant planning and placement in the management of his implant cases.

Dr. Eshamsul is also the coordinator and director of the University of Malaya Certificate of Oral Implantology course, speaker/instructor at many implant courses & workshops in Malaysia. Dr. Eshamsul has given many lectures both within and outside Malaysia. He was an invited speaker at the Asian Academy of Prosthodontics Biennial Conference (2021), Indonesia College of Prosthodontics webinar, Malaysia Oral Implant Association webinar, 6th International Joint Pakistan Prosthodontic Association-Pakistan Association of Orthodontics Conference, Pakistan (2018). He is an active member of MegaGen International Network of Education and Clinical Research (MINEC) and was appointed as MINEC Honoured member in 2020 and a key opinion leader (KOL) for MegaGen implant system. Associate Professor Dr. Eshamsul is also an examiner for the Royal College of Surgeons of England Restorative Specialty Membership & MJDF Examinations. Dr. Eshamsul was one of the winners at the final round MegaMind Clinical Case Competition in conjunction with 15th MegaGen International Symposium 2022 held in Seoul. He is currently the Head of Oral Implantology Unit at the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Malaya.

The information and viewpoints presented in the above news piece or article do not necessarily reflect the official stance or policy of Dental Resource Asia or the DRA Journal. While we strive to ensure the accuracy of our content, Dental Resource Asia (DRA) or DRA Journal cannot guarantee the constant correctness, comprehensiveness, or timeliness of all the information contained within this website or journal.

Please be aware that all product details, product specifications, and data on this website or journal may be modified without prior notice in order to enhance reliability, functionality, design, or for other reasons.

The content contributed by our bloggers or authors represents their personal opinions and is not intended to defame or discredit any religion, ethnic group, club, organisation, company, individual, or any entity or individual.