With the second largest dental market in the world – after the U.S. dental market – and a population of more than 126 million, the Japanese dental community is composed of some 75,000 oral medical institutions, 160,000 dentists and 300,000 oral hygienists.

For about 25 years, its annual market value has been hovering around the same level, close to the 2.6 trillion yen (US$30bn) mark.

It has arguably one of the world’s most stable dental markets and highest quality dental practitioners. In 2018, the dentist-per-100,000-population figure stood at 83.

This enviable position has often been attributed to its high-quality dental education system.

Dental education and curriculum

There are currently 29 dental educational institutions, including: 11 national, one local governmental, and 17 private universities.

Dental undergrads are required to complete compulsory, selective, and elective subjects. In order to graduate, they must at least obtain 188 credits in six or more years. One credit generally translates to 15 – 30 hours spent attending tutorials and lectures, as well as 30 – 45 hours of laboratory work and patient care.

All the dental undergraduates have to take a national board dental examination at the end of a 6-year curriculum, during which they would be required to sit for computer-based tests (CBTs) and objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs) – prior to even starting clinical training.

Road to private practice

The total number of dental students enrolled in 2017 was 2720. The pass rate of national board dental examination is relatively low: around 65–70%. In 2018, the pass rate was 64.5% – 2039 students passed the examination, out of a total of 3159 dental students.

If one intends to practice dentistry in Japan after graduation from dental school, he or she must pass the National Dental Practitioner’s Examination and obtain a license from Japan’s Minister of Health, Labour, and Welfare.

After obtaining a dental license, the fresh graduate must participate in the compulsory residency clinical training program for over one year.

Only upon completing the residency program is the graduate allowed to advance further on the career path as a dentist.

At this juncture, many opt to study postgraduate university courses, or work at hospitals to improve their academic knowledge and technical skills for several years before entering the private practice.

Medical/ Dental insurance system

The vast majority of Japanese dentists practice individually.

A dental or medical institution in Japan is regarded a medical legal entity, which is different from a corporate legal entity. In Japan, the owner and manager of a medical legal entity must be a doctor. The funds required for the establishment of a dental practice entity must be borne by the doctor.

Japan’s national medical insurance is the highest level in the world – Japanese citizens enjoy almost universal medical insurance. The same medical insurance policy applies for both the private and public sector in Japan.

Japan is regarded as a welfare state with a well-developed healthcare system. Introduced in 1961, Japan’s universal health insurance system covers almost all medical and dental treatment and pharmacy care required by the population. Patients, almost across the board, receive treatments at a relatively low cost – the same fee is applied throughout the nation.

Super-ageing population

Owing to a declining birthrate and a growing proportion of older people, the Japanese government has good reason to be concerned at the pace of population aging and the challenges it brings – not just to the medical, but also the dental field.

In 2000, to reduce the burden of its super-ageing population, Japan initiated a “long-term care insurance” to deliver health and welfare services for the elderly.

The use of medical insurance claims to offset dental treatment bills is relatively high as a proportion of total medical insurance coverage, as compared to other developed nations. This has led to Japanese citizens maintaining the habit of visiting their dentist on a regular basis. Patients would normally visit a private clinic, as opposed to a public one, because of its convenient location.

Fierce competition in Japanese dental market

There are few large chain dental group practices that cover the whole country. That said, few dental groups would exceed 20 locations.

Among the nearly 75,000 oral medical institutions in Japan, 80% of them are small-scale clinics with three dental chairs, one medical practitioner, two nurses and one front desk receptionist. The dental private practice market is hence very dense.

In the urban area of Tokyo, for example, you would find more than 13,000 dental practices. There are nearly 120 dental clinics for every 500m distance. Fukuoka, Japan, has a population of about 1 million, but there are 6,000 dental clinics.

Long regarded as belonging to the country’s wealthy class, today’s Japanese dentists are no longer occupying a de facto spot on the economic ladder.

As you can imagine, the high density of dental practices is bound to bring about stiff competition to attract dental patients. Take Fukuoka as an example.

Although there are 6,000 dental practices in Japan’s sixth largest city, 80% of them are small clinics with 3 dental chairs, and the average annual revenue of these small clinics is about 40m yen (~US$2.8m). The monthly sales are around 3.3m yen (US$23,000) excluding rent, staff wages and materials and other expenses. The annual profits of an average dental owner are between 6-8 million yen (US$41,000-56,000).

About 2,000 dental clinics close down in Japan every year, and 2,000 new ones replace them. In the past 20 years, the entire industry has entered a state of stagnant development.

The average income of dentists in Japan today is significantly lower than it was 20 years ago. In 1999, the average income of Japanese dentists was the second in all occupational income rankings in Japan, which was about 20m yen (~$144,000).

Today, the average income of Japanese dentists is around 5.5 million yen, which is about a quarter of what it was 20 years ago.

Professional strata

In terms of level and scale, the service industry in Japan is one of the highest – if not the highest – in the world.

However, in the dental field, many dentists regard themselves firstly as clinicians instead of service providers. This is due to the high degree of both self and societal recognition of their doctor status and occupation. When dentists get together, they are more inclined to discuss dental technology, but rarely touch on the subject of growing their business or improving the patient experience.

For example, you will find a large number of organized societies and associations run by dentists, known as study groups – usually helmed by prominent dentists.

Such academic organizations regularly hold activities every year – of which few and far between are related to management and operation. It seems that the Japanese dentist community at large subscribes to the adage: “If you have the right clinical expertise, the patients will come”.

Operators who attach more importance to management or have opened many chain institutions, although they are also doctors, are often excluded by the “doctor” groups.

This is perhaps more apparent within the academic circles, where an unspoken peer pressure finds the vast majority of members taking a less-than-flattering attitude towards dentists known for marketing or advertising their services.

However, such stratified consciousness within the profession has not stopped the Japanese dentist from spinning creative methods of attracting customers. They include culturally-specific ideas such as Kawaii Orthodontics, Manga-inspired dental services (featured image) and even a Hello Kitty dentist – all banking on local trademarks of ‘cuteness’ and pop culture.

About 2,000 dental clinics close down in Japan every year, and 2,000 new ones replace them. In the past 20 years, the entire industry has entered a state of stagnant development.

What is your Ikegai?

Under the multiple pressures of policy, environment, industry, and customers, today’s Japanese dentists operate in a high-stress environment. Despite this and the country’s notorious work culture, you will find many competent and professional dentists who show their talents through results.

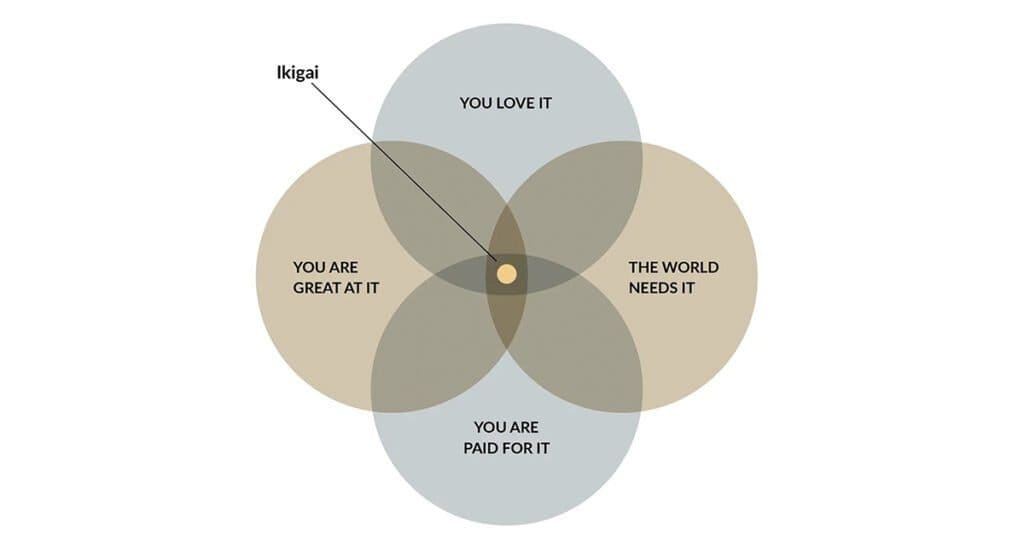

This is testimony to the ‘Ikigai’ mindset that pervades the cultural identity. Although there isn’t any direct English translation of the term, this deeply ingrained Japanese philosophy embodies the pursuit of activities that bring about a sense of purpose and fulfilment in life.

Loosely translated, it is that which gives a person “a reason to get up in the morning” or “gives you meaning in life”.

It lies in the heart of your being – the ‘sweet spot’ if you like – right at the core intersection of all that one represents, including passion, mission, profession and vocation. There are even diagrams that explain the Ikegai concept mainly to non-Japanese, with overlapping circles that represent each sphere of our lives.

Bottom line

Japan’s dental services are well known for their high quality and low prices. For example, a regular visit to a local dentist, which includes consultation and professional dental cleaning, is about a quarter of the price charged in Australia – this is not even taking into account the amount offset by medical insurance for locals.

The low prices obviously come at a high cost for Japanese dentists. Notably, there are 1.5 times more dental clinics than convenience stores in Japan. Considering this country is known for its densely located convenience stores, you can imagine the intense competition between dental operators.

Long regarded as belonging to the country’s wealthy class, today’s Japanese dentists are no longer occupying a de facto spot on the economic ladder. Although the demand for dental treatments has not diminished – in fact it has increased in tandem with the explosion of cosmetic dental treatments – share of that sizeable pie has significantly shrunk, thanks to a crowded marketplace having one of the highest dentist per 100,000 population ratios.

Meanwhile, as many dental clinics struggle to pay the bills, dental schools continue adding to the over-supply of graduates.

The inexorable rise of dental graduates, lower birthrate (meaning fewer patients to go around), and a rigid “business-as-usual” mindset among established dentists, have all conspired to limit, even impair, the invisible hand of market forces to lift the burden off the backs of Japan’s highly pressurised dentists.

Japan’s dentist population has certainly ballooned since the 1950s, when they once faced a shortage. Whether the country’s once lucrative, bustling dental trade will ever return to its heyday when the cost and quality of the oral care service meets the treatment price in a sweet equilibrium is hard to predict.

As of now, the problem of oversupply still hangs in the balance.

The information and viewpoints presented in the above news piece or article do not necessarily reflect the official stance or policy of Dental Resource Asia or the DRA Journal. While we strive to ensure the accuracy of our content, Dental Resource Asia (DRA) or DRA Journal cannot guarantee the constant correctness, comprehensiveness, or timeliness of all the information contained within this website or journal.

Please be aware that all product details, product specifications, and data on this website or journal may be modified without prior notice in order to enhance reliability, functionality, design, or for other reasons.

The content contributed by our bloggers or authors represents their personal opinions and is not intended to defame or discredit any religion, ethnic group, club, organisation, company, individual, or any entity or individual.