This article first appeared in Journal of Digital Orthodontics and is reproduced with permission.

Chris H. Chang, Founder, Beethoven Orthodontic Center Publisher, Journal of Digital Orthodontics

W. Eugene Roberts, Editor-in-Chief, Journal of Digital Orthodontics

Bear C. Chen, Associate Director, Beethoven Orthodontic Center

Lily Y. Chen, Training Resident, Beethoven Orthodontic Center

Abstract

History: An 18yr-9m-old male presented with a Class III malocclusion with negative overjet. His chief complaints were crowding and a protrusive lower lip. He previously rejected treatment with extractions or orthognathic surgery.

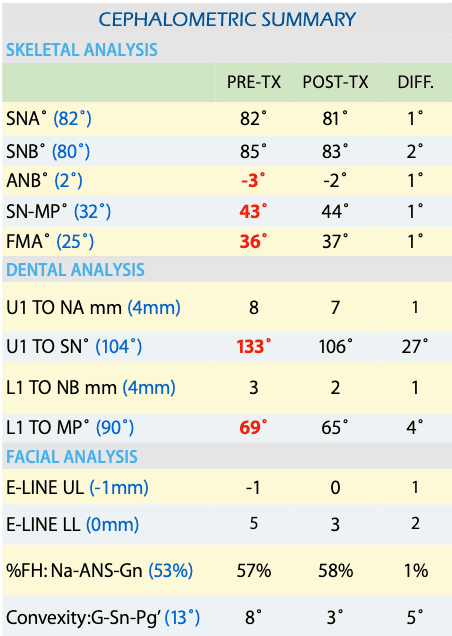

Diagnosis: The cephalometric analysis revealed skeletal Class III (SNA, 82˚; SNB, 85˚; ANB, -3˚), high mandibular angle, flared upper incisors, and retroclined lower incisors. An intraoral examination documented negative overjet, anterior crowding on both arches, and posterior buccal crossbite on U7s. The Discrepancy Index was 32 points.

Treatment: A camouflage, non-surgical approach without extractions was indicated. Buccal shelf (BS) bone screws (2×12-mm, OrthoBoneScrew®, iNewton, Inc., Hsinchu City, Taiwan) were used as anchorage to retract the mandibular dentition, and Class III elastics corrected the intermaxillary discrepancy.Inter-proximal reduction and arch expansion were prescribed in order to provide spaces for arch alignment.

Results: The facial profile was improved with a more balanced lip position. Torque control for the upper and lower incisors was excellent. After 28 months of active treatment, the skeletal Class III malocclusion was corrected to an excellent Cast-Radiograph Evaluation score of 24 points and a Pink & White dental esthetic score of 4.

Conclusions: When correcting skeletal Class III with camouflage treatment, spaces are usually provided through extraction, inter-proximal reduction, and/or arch expansion. However, buccalshelf bone screw anchorage combined with Class III elastics is a powerful weapon to retract the mandibular arch. (J Digital Orthod 2022;67:28-43)

Key words:

Class III malocclusion, camouflage treatment, non-surgical treatment, buccal shelf screw, Class III elastics, clear aligner

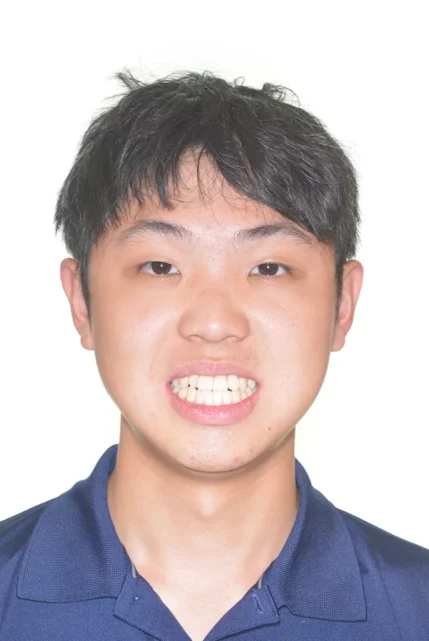

Fig. 1: Pre-treatment facial and intraoral photographs

Introduction

The dental nomenclature for this case report is a modified Palmer notation with four oral quadrants: upper right (UR), upper left (UL), lower right (LR), and lower left (LL). Teeth are numbered 1-8 from the midline in each quadrant.

The prevalence of Angle Class III malocclusion varies among and within differing ethnic groups; however, it is most common among Asians.1 Chinese and Malaysian populations have a high prevalence of Angle Class III malocclusions: 15.69% and 16.59%, respectively. In the United States, the prevalence of Class III malocclusions is only about 1% of the total population; nevertheless, it constitutes about 5% of all orthodontic patients.2,3

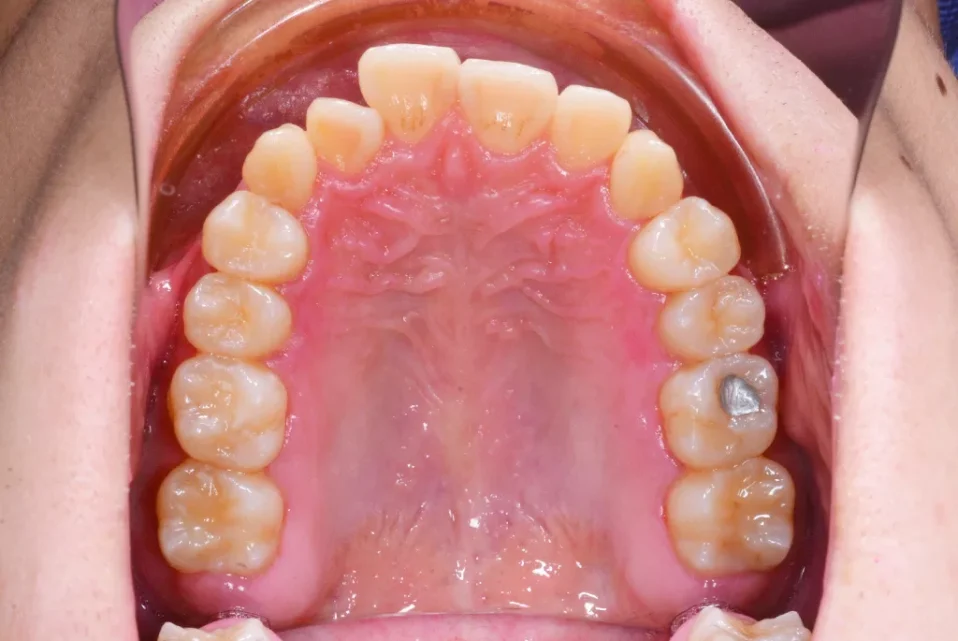

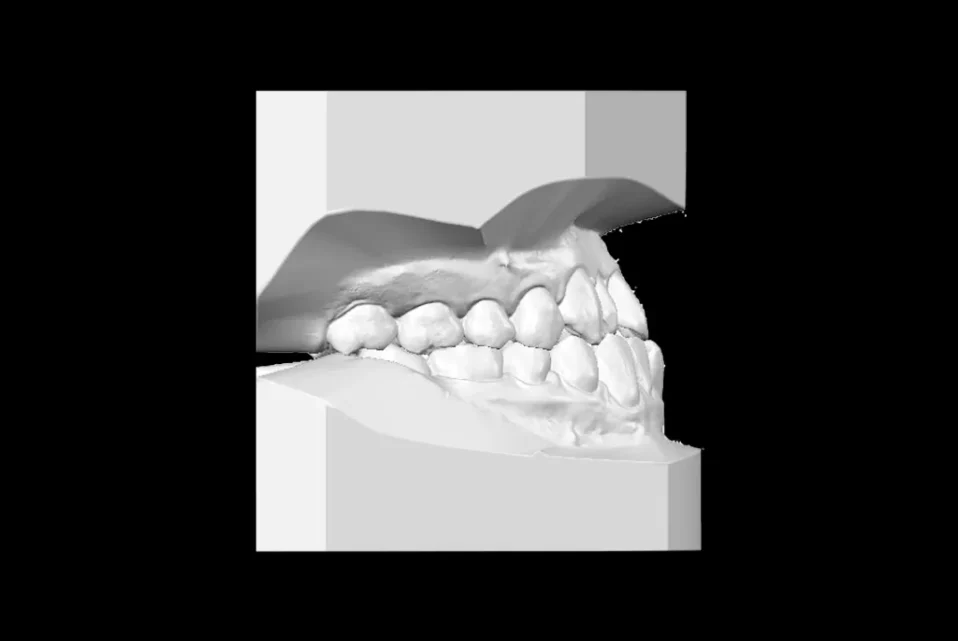

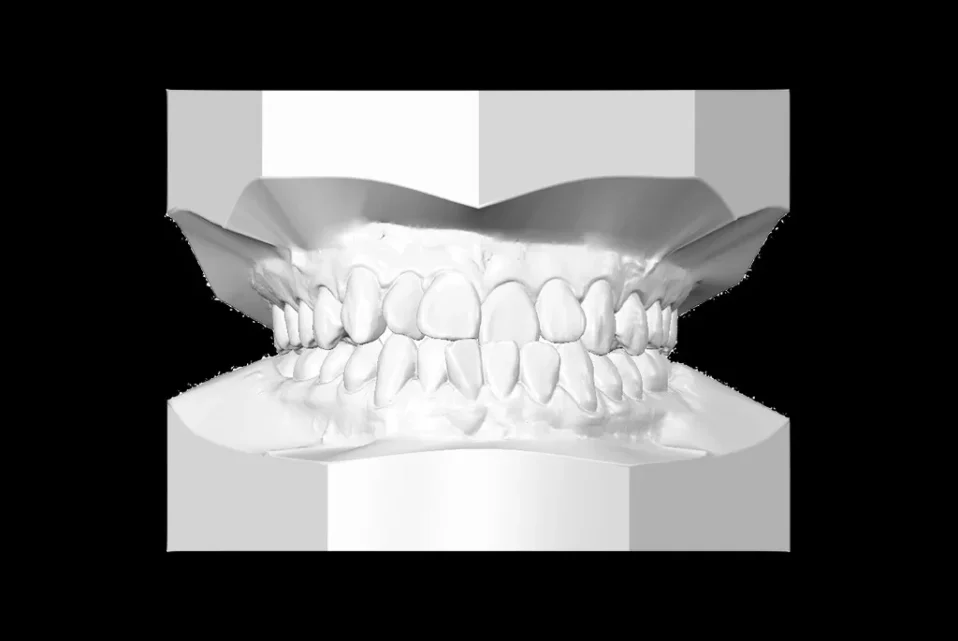

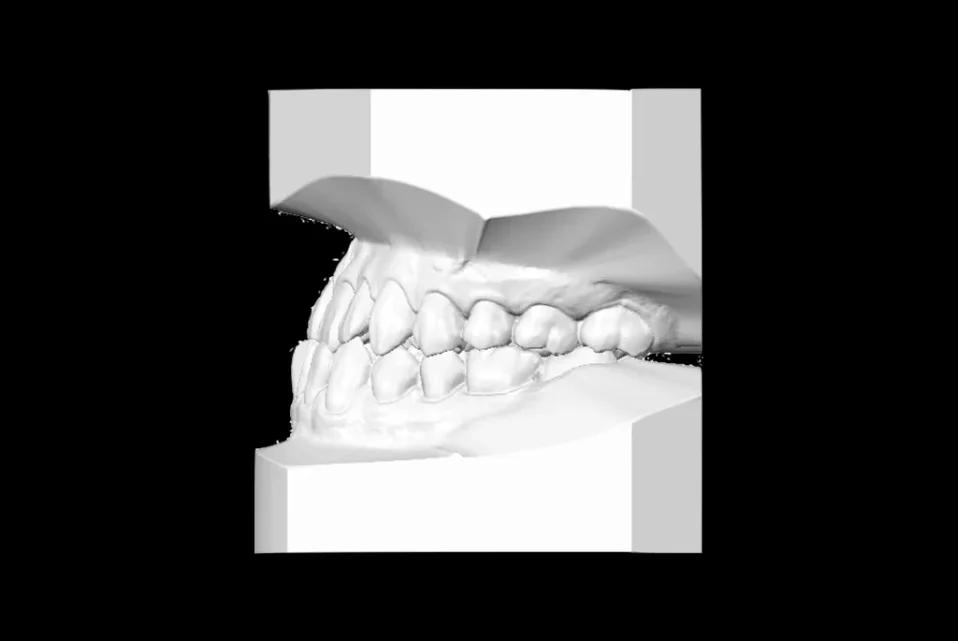

Fig. 2: Pre-treatment study models

In general, Class III malocclusions can be treated by orthodontic camouflage treatment via temporary skeletal anchorage devices (TSADs) with elastics and/or by orthognathic surgery for skeletal correction. However, due to the morbidity, potential complications, and high expense, orthognathic surgery is often declined by Asians. On the contrary, orthodontic camouflage treatment with TSADs is usually preferred.

This case report presents camouflage, non-extraction treatment of a Class III malocclusion using clear aligners. Despite research demonstrating limitations of aligners for correcting skeletal malocclusion,4,5 advancement of aligner material, artificial intelligence, TSAD anchorage, and a proper design of Class III mechanics resulted in a normal occlusion and a balanced esthetic profile.

Diagnosis and Etiology

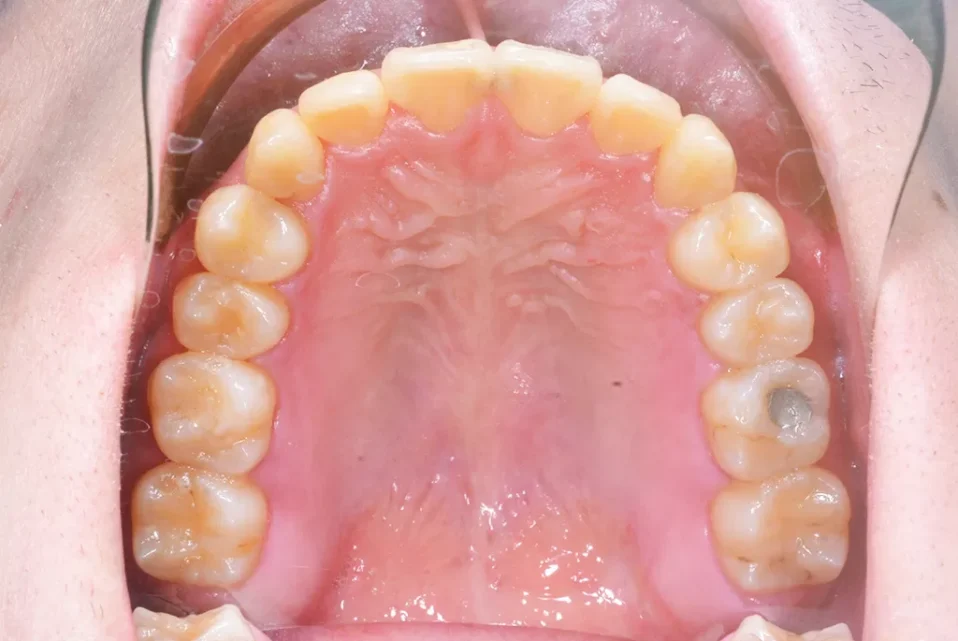

An 18-yr-old male presented for orthodontic evaluation with chief complaints of crowding and a protrusive lower lip (Fig. 1). Medical and dental histories were non-contributory. Plaster casts revealed bilateral Class III canine and molar relationships (Fig. 2). The panoramic radiograph (Fig. 3) showed all four wisdom teeth were missing.

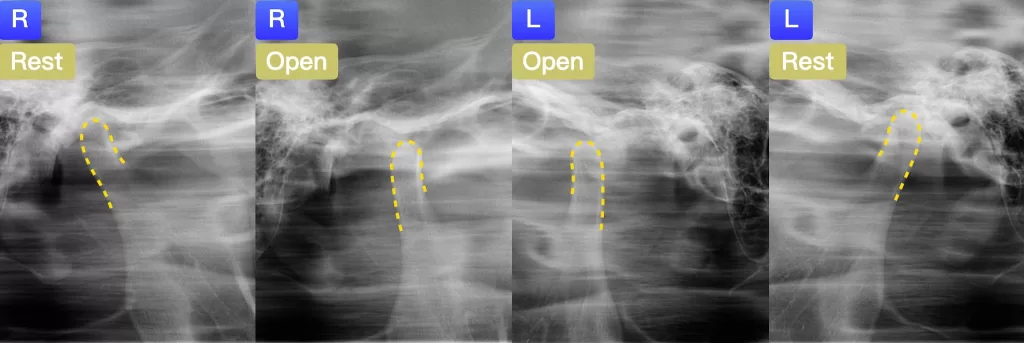

Cephalometric analysis (Table 1) revealed decreased facial convexity (G-Sn-Pg’, 8˚) and a prognathic mandible (SNA, 82˚; SNB, 85˚; ANB -3˚) with a steep mandibular plane angle (SN-MP, 43˚; FMA, 36˚). The upper incisors were flared, and the lower incisors were retroclined (Fig. 4). Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) morphology was normal in the open and closed positions with no temporomandibular dysfunction (TMD) (Fig. 5). An intraoral examination revealed a negative overjet, anterior crowding in both arches, and posterior buccal crossbite on U7s (Fig. 1). The facial profile was nearly straight with a protrusive lower lip (5mm to the E-line). The American Board of Orthodontics (ABO) Discrepancy Index (DI) was 32, as documented in the supplementary Worksheet 1.6

Fig. 4: Pre-treatment cephalometric radiograph

Fig. 5: Pre-treatment transcranial radiographs of the right (R) and left (L) temporomandibular joints (TMJs) in rest and open positions. The mandibular condyles are outlined in yellow.

Treatment Objectives

- Attain ideal overjet and overbite.

- Achieve Class I canine and molar relationships.

- Align both arches, and correct posterior crossbite.

- Improve facial esthetics.

Treatment Alternatives

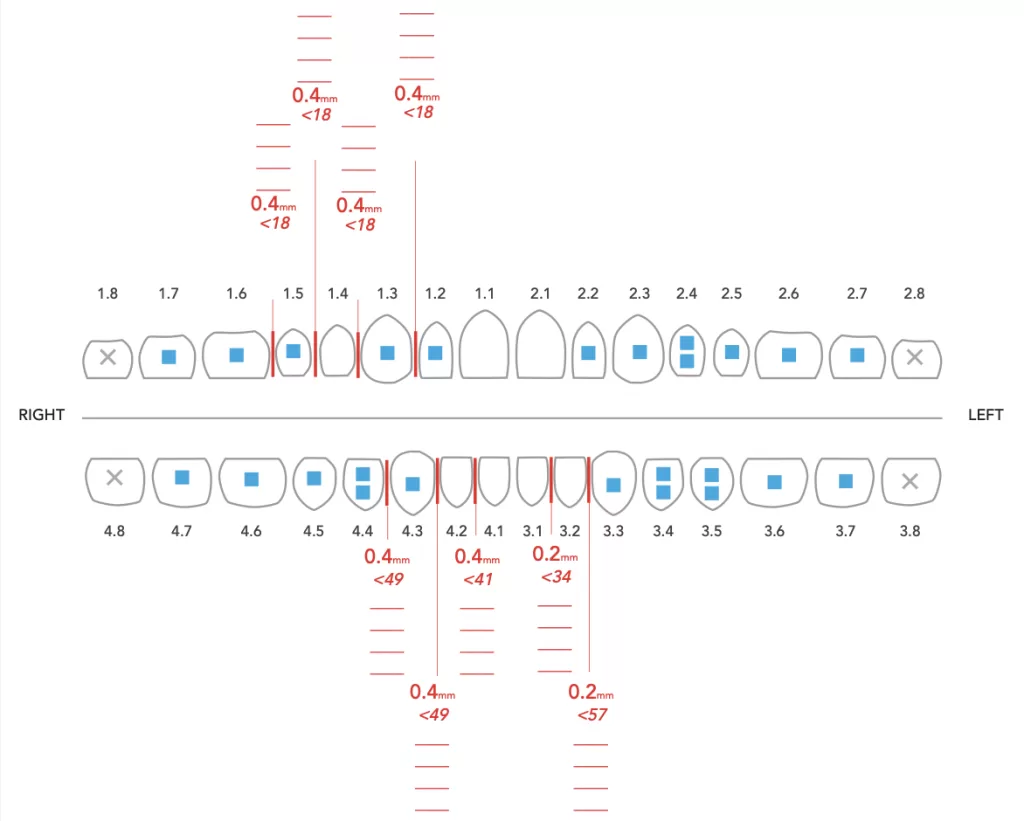

Option 1: A conservative, camouflage approach without extraction that retracts the mandibular arch with buccal shelf (BS) bone screw anchorage and Class III elastics. Create extra space to relieve crowding and retract the mandibular arch by performing 0.4mm inter-proximal reduction (IPR) on each tooth and expanding both maxillary and mandibular arches.

Option 2: Similar camouflage approach to option 1 adding two infrazygomatic crest (IZC) bone screws to retract the maxilla.

Option 3: Camouflage approach with extraction of all four second premolars to provide extra spaces. BS and IZC screws may be required.

Options 1 and 2 are more conservative without extraction, which is suitable for patients with dentophobia. However, expanding the mandibular arch for retraction of the mandible is challenging since the mandibular bone is denser and harder to expand. Option 3 is suitable for relieving anterior crowding, but there is the risk of torque loss on the anterior teeth, which may worsen the retroclination of the mandibular incisors for the current patient. Clear aligner and brackets were both viable for all three options. The patient rejected extraction and preferred clear aligners for better esthetics during the whole orthodontic treatment. Thus, Invisalign® therapy with option 1 protocol was chosen.

<< Back to Contents Menu

EDITOR’S PAGE | MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR | NEWS | PRODUCTS | FEATURE ARTICLES | CLINICAL | Q&A | EXHIBITIONS & CONFERENCES | SLEEP APNOEA

Treatment Progress

The 1st stage was designed to adapt the patient to aligners with no activation. All attachments were bonded in the 2nd stage, and the patient was instructed to use the aligner seater, Chewies. After seating the aligners, the patient should chew on the chewies for a minimum of 5 minutes each time, and the accumulated chewing time per day should be at least an hour for better aligner conformation to the dentition.

Sequential distalization, which moves one tooth at a time, was prescribed throughout the treatment for mandibular retraction, starting from the L7s. Once the L7s were moved 1/3 to 2/3 of the way, movement of the L6s were initiated, and so on. Arch expansion was indicated for both arches in order to provide extra spaces. IPR was prescribed before stages 18, 34, 41, 49, and 57 (Fig. 6).

In the 6th month of treatment (20th stage of aligners), BS screws (2×12-mm, OrthoBoneScrew®, iNewton, Inc., Hsinchu, Taiwan) were inserted for mandibular retraction, and 4.5 oz elastics (Kangaroo 3/16-in, 4.5 oz; Ormco) were hooked from L3 to the BS screw bilaterally (Fig. 7). In the 11th month of treatment (34th stage), power ridges on L2s and L1s were added for better torque control. In the 12th month of treatment (35th stage), Class III elastics were introduced (Fox, 1/4-in, 3.5 oz; Ormco) from U6s to L3s (Fig. 7). Note the precision cuts instead of button cutouts were made on U6s in order to maximize aligner coverage on the teeth. At the end of this set of treatment, the molar relationship was nearly Class I.

Fig. 7: Intraoral photographs at 12 months of treatment. In the 6th month, BS screws were placed and elastics (Kangaroo 3/16-in, 4.5 oz; Ormco) were introduced bilaterally from L3s to the BS screws. In the 12th month, Class III elastics (Fox, 1/4-in, 3.5 oz; Ormco) were hooked bilaterally from the U6s to L3s.

Fig. 8: 62 stages of aligners were designed for the first set of treatment. Difference between predicted and achieved tooth movement (DPATM) after first set of aligners was slight thanks to good patient compliance. However, small finishing details were needed so there was one additional refinement.

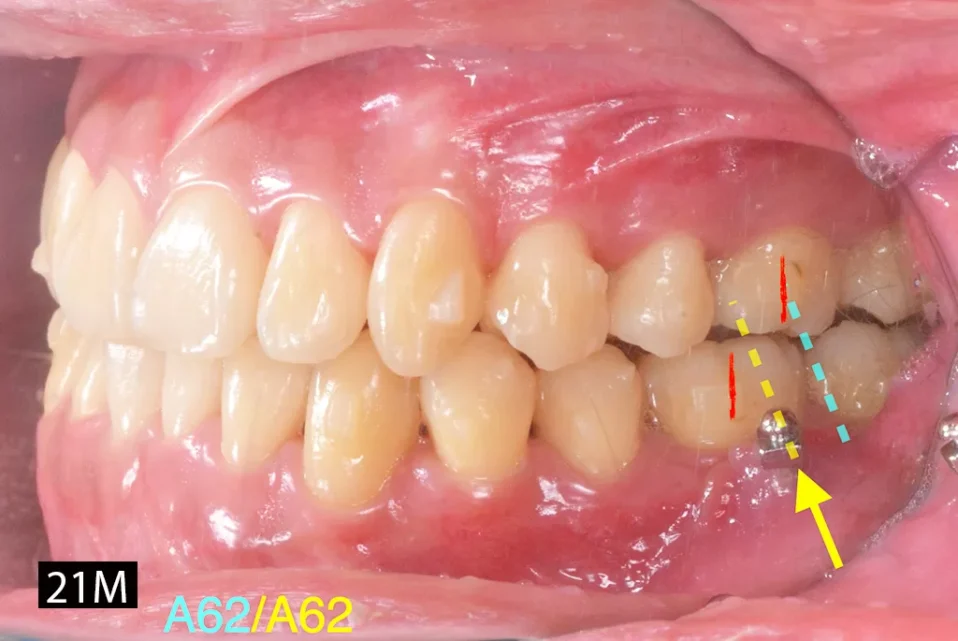

Fig. 9: Note the relative position of the BS screw changed from between LL6 and LL7 (left; blue arrow, dotted line) to being in alignment with LL6 (right; yellow arrow, dotted line) on the buccal side, showing significant retraction of the mandibular arch.

After the first set of aligners (62 stages), the overjet was corrected from negative to a normal positive range. The overbite was also within normal range. Class I canine and molar relationships were achieved (Fig. 8). Note the positions of the molars in relation to the BS screws before and after mandibular retraction (Fig. 9). The BS screws were initially inserted on the buccal side between L6s and L7s. After the first set of treatment, they were positioned on the buccal side of L6s. Differences between predicted and achieved tooth movement (DPATM) were noticed at this stage (Fig. 8). Additional refinement stages were planned in order to improve partial teeth alignment (UR2 and LR1) and to expand the right side of the maxillary arch.

After the refinement, all treatment objectives were achieved. All appliances were removed, and retention was accomplished with maxillary and mandibular clear overlay retainers. Posttreatment records are shown in Figs. 10-13, and the full treatment progress is documented in Figs. 14-16.

Fig. 10: Post-treatment facial and intraoral photographs

Fig. 11: Post-treatment panoramic radiograph

Fig. 12: Post-treatment cephalometric radiograph

Fig. 13: Superimposition of the cephalometric tracings before (black) and after (red) treatment documented good torque control of both maxillary and mandibular incisors, retraction of the mandibular arch, and clockwise rotation of the mandible.

Treatment Results

The facial profile was improved and more harmonious, with the lower lip retruded. Good dental alignment was achieved with bilateral Class I canine and molar relationships despite a minor discrepancy in the occlusal fitting of the posterior section. Anterior and posterior crossbites were both corrected, resulting in better occlusal function (Figs. 10-12). With daily oral functioning after treatment, the posterior intercuspation may be naturally improved after 6 to 12 months.

Superimposed cephalometric tracings (Fig. 13) showed that the flared maxillary incisors were corrected with good torque control. There was decreased mandibular incisor inclination (4˚), which was inevitable after retracting the mandibular arch. However, the non-extraction protocol adopted for this patient successfully limited this side effect on the mandibular incisors. Furthermore, the L6s were retracted by BS screw traction and Class III elastics. The clockwise rotation of the mandible was due to the bite opening to correct the anterior crossbite. The ABO Cast-Radiograph Evaluation (CRE) score was 24 points (Worksheet 2), with major discrepancies in posterior occlusal contacts. The Pink and White esthetic score was 4 due to enlarged U1s tooth size (Worksheet 3).

Fig. 14: Treatment progression is shown the right buccal view from the beginning (0M) to the end of treatment (28M). In the 6th month (6M), BS screws were placed with elastics (Kangaroo, 3/16-in, 4.5 oz; Ormco) hooked bilaterally to retract the mandibular arch. In the 13th month (13M), Class III elastics (Fox, 1/4-in, 3.5 oz; Ormco) were added.

Fig. 15: Treatment progression is shown in the frontal view from the beginning (0M) to the end of treatment (28M). The first set of aligners finished in the 21st month. Refinement was carried out afterwards for adjustments. The overjet improved significantly throughout the treatment.

Fig. 16: Treatment progression is shown in the left buccal view from the beginning (0M) to the end of treatment (28M). Note the relative position of BS screw from 6th month to 21st month in relation to the molars, which shows the retraction of the mandibular arch.

Discussion

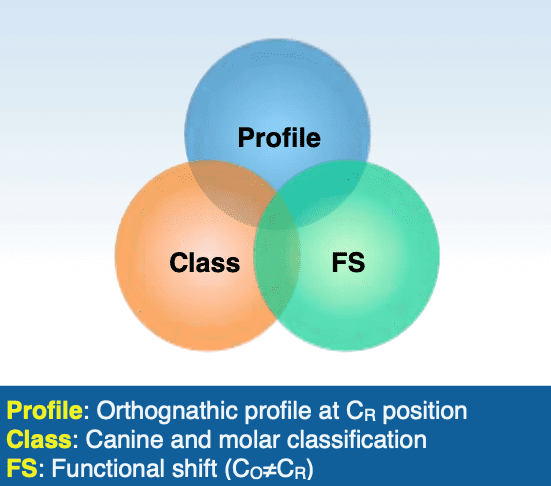

Conservative camouflage treatment for a Class III malocclusion is usually the preferred choice among patients, but the treatment planning is challenging for orthodontists. The 3-Ring Diagnosis (Fig. 17) developed by John Lin is helpful for judging whether a case is suitable for camouflage treatment.7The three determining factors are evaluated under centric relation (CR) position: 1. orthognathic profile, 2. buccal segments that are approximately Class I, and 3. functional shift to centric occlusion (Co) (Fig. 17). The present case fitted none of these criteria; hence, conservative camouflage treatment was very challenging. However, as the patient preferred a non-surgical and non-extraction treatment, Class III elastics, TSADs, and space creation were crucial.

Fig. 17: Lin’s Class III diagnostic system evaluates facial profile and molar classification in CR, as well as the functional shift from CR to CO. If the profile is acceptable in CR, molars are in or near Class I, and there is a significant functional shift, the patient usually can be effectively managed with Class III camouflage treatment.

Class III Elastics

Class III camouflage treatment with or without extraction usually involves intermaxillary Class III elastics with the whole maxillary dentition acting as anchorage to retract the mandibular dentition. According to Newton’s third law of motion, the reaction force leads to protraction of the maxillary arch and labial tipping of the maxillary incisors.8 Thus, resistant moments in the maxillary anterior segment are required via orthodontic devices.9 An advantage of digital orthodontics is designing the torque control for individual teeth after evaluating the rotation of the whole arch. Alternatively, hooking the elastics on TSADs is another way to prevent the adverse effect of Class III elastics.

Placement of TSADs

Compared to intermaxillary Class III elastics, the osseous anchorage of TSADs to retract the mandible prevents the undesirable proclination of the maxillary incisors, which results in a more acute nasolabial angle.10 For severe Class III patients, especially those with an open bite and proclined maxillary incisors, using Class III elastics as the main correcting mechanics is not recommended. Instead, BS screws are indicated.11 One caution to be exercised is that if the slope of the buccal shelf is very steep, the BS screws are placed inter-radicularly. This limits the retraction effect for the whole lower arch due to the contact of the L6 distal root with the screw.However, BS screws are still very powerful in Class III treatments. Note the screw position in relation to the molars in this case (Fig. 9). The BS screw was initially inserted on the buccal side between LL6 and LL7; however, after 15 months, it was in alignment with LL6. The BS screws provided powerful anchorage to retract the mandibular arch. IZC screws are another option to avoid the undesirable proclination of maxillary incisors; they provide osseous anchorage for the Class III elastics.12

Providing Spaces for Arch Retraction

To relieve crowding or perform camouflage arch retraction, extra spaces in the arch are needed. Three common ways to provide extra spaces are: IPR, extraction, and arch expansion.13

In camouflage treatment, extraction is an effective method to produce dental compensation for the skeletal discrepancy.14 Premolars and molars are usually the extraction options in Class III treatment. Premolar extraction is a useful approach to relieve crowding in the anterior segment. However, the disadvantage is more distal tipping of lower incisors compared to extraction of posterior teeth.15 Molar extraction is not useful for relieving anterior crowding, and closing extraction spaces is time-consuming, but it creates more space (10-11mm) for retraction compared to premolar extraction (7mm).14

Arch expansion is feasible with Invisalign®to resolve crowding and anteroposterior problems.16,17An 1mm increase in the inter-molar width will allow for approximately 0.6mm of space creation within the arch.13 According to Ali et al.,18 dental arch expansion should be limited to 2-3 mm per quadrant in order to minimize the risk of relapse and gingival recession. However, overcorrection of expansion in the maxillary posterior segment is suggested in order to achieve the desired expansion results. The accuracy of planned maxillary arch expansion with Invisalign® is 72.8%, while the accuracy for mandible was more precise, which is 87.7%.19

Conclusions

Skeletal Class III malocclusions often require extraction to provide space for mandibular distalization. However, when the patient refuses extraction, other methods of space creation such as IPR, arch expansion, and retraction can be adopted. When correcting anterior crossbite, buccal shelf screws and Class III elastics are viable choices to achieve a successful outcome.

References

- Ishii H, Morita S, Takeuchi Y, Nakamura S. Treatment effect of combined maxillary protraction and chincap appliance in severe skeletal Class III cases. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1987;92(4):304-312.

- Graber TM, Vanarsdall RL, Vig KWL. Orthodontics. Current Principles and Techniques,4rth ed. St Louis: Mosby. 2005. p. 565.

- Jaradat M. An overview of Class III malocclusion (prevalence, etiology and management). J Adv Med Med Res 2018;25(7):1–13.

- Zheng M, Liu R, Ni Z, Yu Z. Efficiency, effectiveness and treatment stability of clear aligners: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthod Craniofac Res 2017;20(3):127–33.

- Papadimitriou A, Mousoulea S, Gkantidis N, Kloukos D. Clinical effectiveness of Invisalign® orthodontic treatment: a systematic review. Prog Orthod 2018;19(1):1-24.

- Cangialosi T, Riolo M, Owens S, Dykhouse V, Moffitt A, Grubb J et al. The ABO discrepancy index: a measure of case complexity. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthoped 2004;125(3):270-8.

- Lin JJ. Creative orthodontics blending the Damon System & TADs to manage difficult malocclusion. 3rd ed. Taipei, Taiwan: Yong Chieh; 2017. p. 259-276.

- Ferreira FPC, Goulart M da S, de Almeida-Pedrin RR, Conti AC de CF, Cardoso M de A. Treatment of Class III malocclusion: atypical extraction protocol. Case Rep Dent 2017:ID 4652685.

- Hu H, Chen J, Guo J, Li F, Liu Z, He S, Zou S. Distalization of the mandibular dentition of an adult with a skeletal Class III malocclusion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2012;142(6):854–62.

- Huang S, Chang CH, Roberts WE. A severe skeletal Class III open bite malocclusion treated with nonsurgical approach. Int J Orthod Implantol 2011;24:28–39.

- Lin JJ. Treatment of Severe ClassIII with buccal shelf mini-screws. News & Trends in Orthod 2010;18:3-12.

- Lin JJ. The most effective and simplest ways of treating severe Class III, without extraction or surgery. Int J Orthod Implantol 2013;33:4-18.

- O’higgins E, Lee R. How Much Space is Created from Expansion or Premolar Extraction?. Journal of Orthodontics 2000;27(1):11-13.

- Cheng J, Chang CH, Roberts WE. Severe Class III open bite malocclusion: conservative correction with lower first molar extraction. J Digit Orthod 2021;61:50-66.

- Akhoon AB, Mushtaq M, Ishaq A Borderline Class III patient and treatment options: A comprehensive review. Int J Med Heal Res 2018;4(2):14–6.

- Womack WR, Ahn JH, Ammari Z, Castillo A. A new approach to correction of crowding. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2002;122:310–316.

- Giancotti A, Mampieri G. Unilateral canine crossbite correc- tion in adults using the Invisalign method: a case report. Orthodontics (Chic.) 2012;13:122–127.

- Ali SA, Miethke HR. Invisalign, an innovative invisible orthodontic appliance to correct malocclusions: advantages and limitations. Dent Update 2012;39:254–256, 258–260.

- Houle JP, Piedade L, Todescan R Jr., Pinheiro FH. The predictability of transverse changes with Invisalign. Angle Orthod 2017;87(1):19-24.

The information and viewpoints presented in the above news piece or article do not necessarily reflect the official stance or policy of Dental Resource Asia or the DRA Journal. While we strive to ensure the accuracy of our content, Dental Resource Asia (DRA) or DRA Journal cannot guarantee the constant correctness, comprehensiveness, or timeliness of all the information contained within this website or journal.

Please be aware that all product details, product specifications, and data on this website or journal may be modified without prior notice in order to enhance reliability, functionality, design, or for other reasons.

The content contributed by our bloggers or authors represents their personal opinions and is not intended to defame or discredit any religion, ethnic group, club, organisation, company, individual, or any entity or individual.